Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean, or C. E. W. Bean, was an Australian journalist, war correspondent, and historian. Bean, the distinguished editor of the 12-volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, wrote Volumes 1 and V1, as they were the topics he covered in the Australian Imperial Force at Gallipoli, France, and Belgium. Bean was born in Bathurst, New South Wales. His father was in Australia for six years as headmaster of All Saints College Bathurst. Charles attended school from 1886 until 1889 when his father resigned due to poor health and returned to England with the family. For two years, Bean spent the summers in Oxford and winters in Brussels, where he learned French and drawing despite winning a scholarship to Hertford College. [ Oxford B. A. 1902 to B. C. L., 1904 M. A., 1905] He enjoyed reading the classics but favored history over philosophy or law.

Charles started by simplifying his craft which someone with average intelligence could understand. He returned to Australia in 1904, worked as a lawyer, and was an assistant master at Sydney Grammar School. He also wrote articles for Evening News. In 1905-07, he wrote a book about Australia and what it was like for a returning native. Charles penned eight articles for the Sydney Morning Herald from June to July 1907 and decided to write for a living. Instead of teaching or practicing law, the Sydney Morning Herald took him on as a junior reporter in January 1908. In September 1914, with the outbreak of World War One, Bean was selected by ballot as an official war correspondent, made an Honorary Captain in the AIF, and then traveled to Egypt with the Australian Imperial Force.

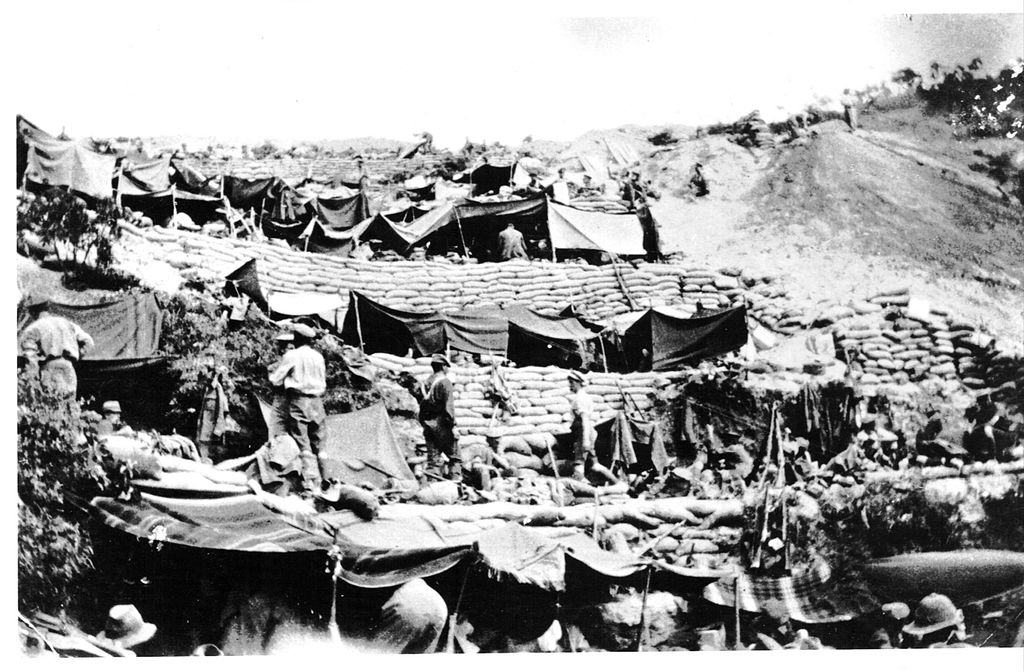

Bean landed on Anzac Cove at 10 am on 25 April 1915 and stayed on Gallipoli until the evacuation… He was the first journalist to go ashore while taking notes and making sketches about the war. Bean would sit in his dugout and write in his diary about the 1100 photographs he took with the journal of his accounts of events at Gallipoli at hand, a bullet hit him in the right leg, but he didn’t want to go to the hospital ship to have it dressed every day. He wanted to go out and report the fighting. He was the only correspondent on the peninsula from April to December. When the Anzacs withdrew from Gallipoli, Bean edited the Anzac Book because the Australians were located in France in 1916. Bean was with them and would work with war correspondents Frank Hurley and Hubert Wilkins.

He was there where the action was more than any other Australian in the First World War. He left Gallipoli two days before the evacuation, partnered with the Australian Historical Mission, and became a legend. In his own right, by helping the troops on the front line and coordinating activity between the branches of the military services on each flank with the allied forces, he reported on the troops. During this time on the frontline, with the captured German soldiers providing misleading information, Bean decided to plan for the post-war upholding of Anzac’s legacy.

The foundation of the museum and memorial was to be built. Meanwhile, Bean was in France observing the AIF while sending back dispatches published as [Letters from France]. On 16 May 1917, the Australian War Records Section was established to keep a record of documents and relics. Connected to the section was the Australian Salvage Corps which would select items from the battlefield that interested them. Bean got paid a 15-pound clothing allowance,” had a horse and saddle, and his sidekick, Private Arthur Bazley, was assigned as Bean’s Batman and became good friends over the years.

As Bean’s influence grew as the war proceeded, he lobbied with Keith Murdoch,, father of Rupert Murdoch, to deny General John Monash an appointment to the Australian Corps in 1918 because he was Jewish. During that time, there was ingrained prejudice against him for not being manly enough. Bean wrote in his diary, “We do not want Australia represented by man mainly because of their ability, natural and inborn in Jews, to push themselves.” It was an anti-semitic sentiment held by the elites at that time despite Bean favoring Australian Chief of General Staff Brudenell White, who had successfully planned the withdrawal from Gallipoli.

In 1916, the British War Cabinet decided that official historians should have access to the war diaries of the British Army, which had been fighting on two fronts. While Bean gave access to the resources, he did not compromise his values for political expediency or personal gain.. Bean’s account was terrible from an Imperial position for his stance, and he was denied decorations by King George V, although he was recommended twice during the war. Bean was never offered a knighthood because, many years later, he declined the presentation. In 1919, the Australian Historical Mission returned to the Gallipoli peninsula to revisit the battlefields and the mission Bean led in 1915.

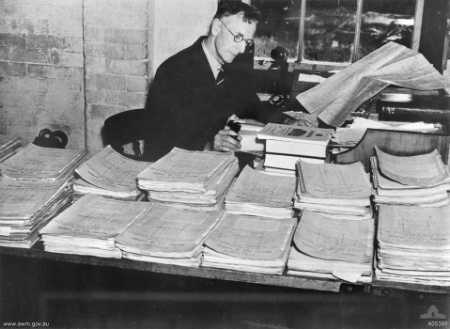

At one of the sites of the famous battles, Lone Pine and the Nek, he found the bones of the light horsemen that were lost at war. When Bean returned to Australia in 1919, he started to work with a team of researchers on the official history of the first volume, which covered most of the AIF and the landing at Anzac Cove and was published in 1921. It would be 21 years before the 12 manuscripts were printed, while six volumes by Bean were published in 1946[ Anzac to Amiens]. Because it was the only book he owned the copyright of and received royalties from, Bean did various jobs, was employed by the Department of Information as a liaison between heads of staff, and eventually became chairman 1942 of the Commonwealth Archives Committee. In 1964, Bean died at 84 and will always be remembered as a legend for keeping the Spirit of the Anzacs alive.

References

By not stated (Photo from The War Illustrated, 19 June 1915.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Photographer: L-Cpl. Arthur Robert Henry Joyner (1st Division Signal Company, killed 5 December 1916 at Bazentin, Somme) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By user: GrahamBould [Public domain, Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

George Washington Lambert [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By Not stated (http://www.awm.gov.au/database/collection.asp) [Public domain], via Wikimedia